Cure4CF Update

Did you know that one of our Cure4CF Ambassadors is an emerging scientist with an interest in bacteriophages?

Mae has recently completed her degree in Forensic Science and has a keen interest in research, hoping to work as a forensic chemist when she completes her studies. Recently, Mae shared with us a case report that she really enjoyed. Published in 2019 in Infection, the article explored the use of bacteriophage therapy in a 26-year-old CF patient who became very unwell and was found to have two multidrug-resistant (MDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa organisms. One was a mucoid strain, and one was a non-mucoid strain. Most pseudomonas starts out as non-mucoid strains, but they can mutate and adapt to their environment and become a mucoid strain which are most often very hard to treat with antibiotics. The bacteria can coat itself with a sugar called alginate which serves to protect it from eradication.

What is a mucoid strain of bacteria?

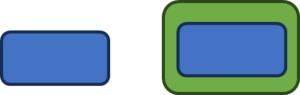

The blue rectangle represents a regular non-mucoid bacterium and as you can see when it develops into a mucoid strain, the protective green layer develops around the bacterium making it much harder to treat.

The blue rectangle represents a regular non-mucoid bacterium and as you can see when it develops into a mucoid strain, the protective green layer develops around the bacterium making it much harder to treat.

You can see it in the image to the left in a real culture plate.

You can see it in the image to the left in a real culture plate.

The patient needed a lung transplant and was very unwell but could not receive a lung transplant with the severe infection. The team was able to apply and receive approval for emergency treatment with an investigational bacteriophage therapy. This was a cocktail of four different bacteriophages delivered intravenously.

Phage Cocktail for Pseudomonas – Did it work?

Following an 8-week treatment period with the bacteriophage therapy combined with antibiotics the patient significantly improved and her infection had resolved. Importantly there was no recurrence of P. aeruginosa for 100 days following the bacteriophage therapy. The treatment was observed to be safe with no recorded side effects and enabled the patient to have a successful bilateral lung transplant 9 months later.

During the therapy the team monitored both mucoid and non-mucoid strains and how they responded to the bacteriophage and the antibiotics. Interestingly at different times the bacteria isolated were susceptible to antibiotics which may suggest that bacteriophages can help restore antibiotic effectiveness. At one point in the treatment program one of the strains was resistant to the bacteriophage therapy but was able to be treated effectively with the combined antibiotics. So, whilst this therapy is promising, it does suggest that resistance with bacteriophages is possible. One of the amazing properties of bacteriophages, that is not shared with antibiotics, is that they can also adapt to their environment and change and therefore we hope they will offer improved long term therapy options for infection in CF.

Mae explains:

“This kind of treatment would be beneficial for the CF community. Bacteriophage therapies have the potential to move us closer to successfully treating colonised bacterial infections and MDR infections. Better yet, the specificity of these treatments (they only act against a range of bad bacteria) means that the symptoms would be much less severe than regular antibiotics. Our guts will be smiling!

Whilst this treatment will be very impactful, it still has a long way to go before we can use it as safely and effectively as possible”.

Cure4CF are so excited to be bringing the first phase 1 clinical trial of bacteriophage therapy for young people with the team at Westmead Childrens Hospital. Read more about the work here.

Cure4CF Resarcher Dr Jagdev Singh added:

“Just like Mae, we are truly excited and hopeful about the prospects of what these tiny viruses can do to help us fight infections that are difficult to treat with conventional antibiotics. Bacteria will naturally develop strategies to evade antibiotics; it is in their nature to evolve protective mechanisms, such as developing green layers around themselves to make it harder for antibiotics to be effective.

This is where nature has provided us with a potential solution. Bacteriophages, natural bacterial predators that are only interested in bacteria, have, over billions of years, developed a unique ability to evolve and adapt alongside bacteria to continue being effective against them.

Through our work, supported by the Cure4CF Foundation and ambassadors like Mae, we hope to test simple and effective ways to deliver bacteriophages. We carefully select the most effective bacteriophages to treat lung infections in children living with CF and deliver them through a technique called nebulisation, a method familiar to most families with children with CF. Often, these children have had these infections for years, impacting not only their lungs and life span but also their ability to exercise, play, or attend school regularly like any other child.

As part of our phase 1 clinical trial, which aims to demonstrate that bacteriophage treatment can be delivered safely, we hope to open more doors for researchers to explore the vast potential of the world of bacteriophages in a clinical setting.

Our aspiration is that someday, any child struggling with a lung infection that is difficult to treat with antibiotics will have the option of bacteriophages as a treatment option.